He–Prince–didn’t exactly come to me in a cloud of purple divinity and command me to do so, mind you. I had been on Tumblr, largely out of pedagogical dedication, sporadically reblogging things and scrolling and refreshing pages for hours on end, since the end of 2011. I was a late-adopter of social media, having only joined Facebook in 2009 because as the youngest member of the Executive Committee of the Association of Black Sociologists at the time, I was drafted to make sure we “reached out to the young folks on the face books.” I joined Twitter in 2012 because I lost a bet with former McNair mentee Kimber Thomas, and even then I kept my account private and tweeted sundries when the mood struck.

He–Prince–didn’t exactly come to me in a cloud of purple divinity and command me to do so, mind you. I had been on Tumblr, largely out of pedagogical dedication, sporadically reblogging things and scrolling and refreshing pages for hours on end, since the end of 2011. I was a late-adopter of social media, having only joined Facebook in 2009 because as the youngest member of the Executive Committee of the Association of Black Sociologists at the time, I was drafted to make sure we “reached out to the young folks on the face books.” I joined Twitter in 2012 because I lost a bet with former McNair mentee Kimber Thomas, and even then I kept my account private and tweeted sundries when the mood struck.

“An Idea of Change”: Marco Pavé and the Politicization of Memphis Hip-Hop

Art is always already personal and political. Memphis native Marco Pavé’s recently released mixtape, Obscure Reality, and his community work in and beyond his neighborhood, exemplify this dual function of art, as well as the possibilities of art to reflect and instigate social change. The 21-year-old rapper operates squarely in the tradition of Memphis hip-hop artists before him, who have frequently used their work to tell untold stories, reckon with the ghosts of King and civil rights, and highlight the city’s current social position. Yet, as part of the center of a bourgeoning movement of young creatives and intellectuals speaking back to the city’s unequal power relationships, Pavé marshals his art for direct action and transformation of his neighborhood and city. [Read more…]

Art is always already personal and political. Memphis native Marco Pavé’s recently released mixtape, Obscure Reality, and his community work in and beyond his neighborhood, exemplify this dual function of art, as well as the possibilities of art to reflect and instigate social change. The 21-year-old rapper operates squarely in the tradition of Memphis hip-hop artists before him, who have frequently used their work to tell untold stories, reckon with the ghosts of King and civil rights, and highlight the city’s current social position. Yet, as part of the center of a bourgeoning movement of young creatives and intellectuals speaking back to the city’s unequal power relationships, Pavé marshals his art for direct action and transformation of his neighborhood and city. [Read more…]

Mississippi Prometheus: Big K.R.I.T. and The Southern Black/Rap Snapback

May 21, 2014

Awnaw, hell naw, mane, y’all done up and done it/…them country boys on the rise – Nappy Roots, “Awnaw”

Stop being rapper racists/region haters/…This is southern face it/if we too simple/then y’all don’t get the basics – Lil’ Wayne, “Shooter”

Hope the hook wasn’t too simple/either way, nigga, I wrote it/yes, I made the beat/yes, I made the track…I don’t fall in line/I define what’s rhyme – Big K.R.I.T., “Mt. Olympus”*

“I swear a country nigga snap…” – Big K.R.I.T., “Mt. Olympus”

While “country” is oft-times a pejorative term meant to denote someone’s greenness, lack of sophistication, or backwardness, black southerners have long used country to describe an existence rooted in dirt and power, and the ability to survive and maneuver through a world that would rather them not. Still, in its use as an insult, “country” reflects black Americans’ discomfort with southern blackness and its linkages to historical anxieties about the trauma of slavery, black male emasculation, the dehumanizing violence of Jim Crow, and the continued anti-modernity of the (rural) South. Whether the players are Richard Wright and Zora Neale Hurston, Spike Lee and Tyler Perry, or Ice-T and Soulja Boy, as I argue in This Ain’t Chicago, in the aggregate drama of black representation, black folks would rather excise all country niggas–who are seen as reminders of a past of subjugation–from the narrative of the race.

I Guess I’ll See You Next Lifetime: Geographies of Time Travel in Kiese Laymon’s Long Division

24 Feb 2014

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately…” -Thoreau, 1854

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” -Faulkner, 1950

“And I can feel it for sure/I been here before.” -Teena Marie, 1979

“I guess I’ll see you next lifetime/I’m gone be there.” – Erykah Badu, 1997

“I’m going live (forever and ever and ever) from the underground.” – Big K.R.I.T., 2013

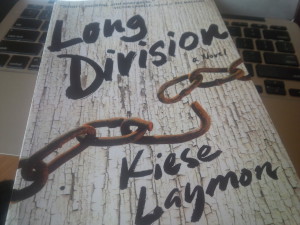

The mathematics of what this is and is not: review < musing.

One time I was in a philosophy dissertation defense about Levinas, and one of the philosophy professors in attendance asked the defending candidate, “If I were walking down the street, how would I know transubstantiation when I saw it?” The candidate’s answer was, “I’m not sure that you would, but you just would.” Some folks thought it was an absurd question for various reasons, and still others thought the answer was absurd for various reasons, but I understood then, and was reminded of the exchange many times reading Kiese Laymon’s Long Division. Reading it is like watching your ontology walk past you on the street like déjà vu and pointing at it gaped-mouthed and speechless, trying to name it because you know it, but you can’t because it’s way bigger than you are, even though it is, in fact, only little ol’ you walking by. Reading it does this to you because the book is like the blues, traveling easy across time, sometimes on the downbeat, but usually on the 2 & 4, and sometimes in between.

One time I was in a philosophy dissertation defense about Levinas, and one of the philosophy professors in attendance asked the defending candidate, “If I were walking down the street, how would I know transubstantiation when I saw it?” The candidate’s answer was, “I’m not sure that you would, but you just would.” Some folks thought it was an absurd question for various reasons, and still others thought the answer was absurd for various reasons, but I understood then, and was reminded of the exchange many times reading Kiese Laymon’s Long Division. Reading it is like watching your ontology walk past you on the street like déjà vu and pointing at it gaped-mouthed and speechless, trying to name it because you know it, but you can’t because it’s way bigger than you are, even though it is, in fact, only little ol’ you walking by. Reading it does this to you because the book is like the blues, traveling easy across time, sometimes on the downbeat, but usually on the 2 & 4, and sometimes in between.

I thought after the third reading of Long Division I’d be qualified to speak on it, but I still ain’t, so this is less a review, more a musing on the thing. For almost nine months, I’ve avoided most discussions and reviews of the text, other than Laymon’s own, like TV show fans avoid spoiler alerts. For a black southern reader, Long Division requires some quiet reckoning with one’s interiority as well as some raucous, in-your-face group discussions, which can but usually cannot happen on the Internet. Yet, I can say with absolute certainty that Long Division has, in one text and with some of the trillest sentences ever, answered the call of southern hip-hop and black southern film to have more voices at the table singing out about who we are across space, place, and time. For a people, a place, and spaces, who, as André 3000 instructs us, got something to say, Long Division claps, bangs, raps, and speaks loud in the darkness, such that the message reverberates through the now, the past, and the future in the civil rights, rural, urban, contemporary, Katrina, Gulf Coast, and Melahatchie Souths.

Even though we make overtures to the intersection of time and space, in practice, temporality and geography are usually considered separately. In Long Division, though, time, space, and place converge as characters, plot devices, words, paragraphs, and ellipses. Seriously considering time and space together requires a bold affirmation of and careful attention to people and places, and Laymon offers that for black southerners and/in the South. The novel is haunted, in fact, by time and space, as the past is and interrupts the characters perpetually as they strive to write and change their futures. The three temporal Souths in Long Division coincide with the civil rights South, the crack South, and the post-Katrina South, which are simultaneously times and spaces and places. These moments are each apt representations of moments of space/time rupture—where Jackson, Glendora, Birmingham, and Highway 51 ran smack into each other; where crack and your cousin from Chicago who was “in a gang” and weapons and cats with one red Fila and one black British Knight on ran smack into Clarksdale, Little Rock, and Biloxi; where oil and orchestrated disaster and race and region and religion and rurality ran smack into the Gulf Coast and the lower ninth ward. With Chicago looming in the backdrop as a distant urban space that is/was and is/was not the South, we are invited to time travel, to traverse these Souths, the rural, urban, and small-town Souths. We are encouraged to think about the piney woods with all of their questions and answers; Melahatchie and Jackson; the Mississippi Gulf Coast and New Orleans. But from civil rights to crack to Katrina, we can move back and forth through time and end up in the same place and space because the structures are the same. Yet, Laymon’s narrative rejects this fixed outcome, as he asserts that through our voices, we might write a future that pushes against, stretches, and bends the structures of power designed to limit our freedom. To create opportunities where there are inherent constraints. We talk about finding our voices, but we talk less about how finding our voices means finding and writing freedom for ourselves and others.

An aside: In many ways, Long Division could only ever be written about the black South, because who time travels more than black southerners? Big K.R.I.T. time travels in “Praying Man.” When Kindred’s Dana goes back, Butler sends her to the South, to slavery. Erykah Badu is sure she’ll be there next lifetime. When I walk on the University of Mississippi campus and am greeted by towering Confederate statues or accidentally bump into Meredith’s statue behind the Lyceum, I time travel. When the University implicitly encourages students to put a noose on Meredith’s statue, I time travel. Time travel is necessitated by rupture, and therefore we are constantly in a state of temporal movement–or of flight like Morrison’s Milkman, or underground like Ellison’s protagonist and Laymon’s protagonists–because of our experiences and histories as black folks in the South.

Treatments of the South often fix the region in time and space. When return migrants are eager to “come home” to the South, they remember a respectable imagined community of all-black neighborhoods with doctors staying next door to factory workers. When southern expatriates in the North or West who plan never to return talk about the South, they point to the Jena 6 and Trayvon Martin and imagine country road ramblings and edge-of-town lynchings. When white Yankees think on the South, they remind themselves of their own relative goodness compared to Phil Robertson. The South is forever rural, forever 1964, sometimes forever slavery, which obscures the way it both is and is not those things. To say that the South ain’t changed and is all country is not true. But then neither is saying it has changed and is new and shiny and cosmopolitan. Long Division allows us to step directly into these tensions and be squeezed and pulled by the contradictions as we roller-coaster-jolt from 2013 to 1985 to 1964 and back again.

As if anything could be beyond what Laymon has done for race, temporality, geography, and the South—as well as for the real and transhistorical black southerner—there is also what Long Division does for questions of love, death, and dying. Across cities/Cities, there is the looming and encompassing quality of love that bends sexuality and familial boundaries. But there is also dying as the liminal space between love/life and death. In any given moment, Long Division argues, as long as one is loving, she or he can transcend the messiness that is a blues dying and get on to a blues death so one can be born and get back to living and loving again. Yet, the novel reminds us that sometimes it is extraordinarily hard to give up love for a greater good, or to delay love until the next lifetime, or to choose between things we love. As (semi-)free agents, we make these choices within a context of constraints and hostile structures, but we are under an extraordinary amount of pressure to get the choice right. Our future, and our past, depend upon it.

I imagine I’ll be writing, reading, reading about, and teaching Long Division for a long time. It is part of that hard work in the shed, of crafting and loving the region and the race, and of giving voice to ourselves to ensure a future freedom that we create. It is undoubtedly an invitation (and in many ways an imperative) for all of us with these black southern ontologies to get in the shed and get this work.

Drake Plays the Blues: “Down South” and the Black Imaginary in “Worst Behavior”

December 31, 2013

http://vimeo.com/79018443

“Down South” is a ubiquitous trope in the black American imagination, used to conjure actual and fictive remembrances of a space and time removed from and outside of modernity, the anti-present. It’s an imagined space through which one, usually a seasonal migrator or former southerner, or an altogether non-southerner, can safely navigate a number of complexities of personal history, home, memory, and angst. With the 10-minute video for “Worst Behavior” Drake uses the notion of Down South, and Memphis in particular, to narrate broader ideas about authenticity, masculinity, fatherhood, home, and longing.

man, muhfuckas neva loved us

Cash Money Records afforded Aubrey Drake Graham, the middle class biracial Jewish Canadian kid of Degrassi fame, a black audience and black working class authenticity through proximity to some New Orleans hot boys. This proximity, along with his rap prowess, has afforded Drake some space to blossom in a game that seemed to not yet have room for him. Still, jokes about Drake abound, with the rapper frequently making the problematical Top 10 Softest Rappers in the Game list and an infamous meme about his Dada outfit circulating through the interwebs in summer 2013. Further, Cash Money has not completely eradicated the artist’s authenticity troubles. Grumbles about “Started from the Bottom”–how dare a middle class Canadian kid talk about starting from the bottom?–revealed the intraracial class dynamics of the prerequisites for authenticity. That is, one might now be extraordinarily wealthy, but as long as she or he started from a legible bottom–say, the Hollygrove neighborhood of New Orleans–one can enjoy unlimited authenticity, no matter how pop one becomes.

“Playing on the One”: Memphis Soul from Teenie Hodges to Tonya Dyson

November 15, 2013

Review of Susanna Vapnek’s Mabon Teenie Hodges: A Portrait of a Memphis Soul Original and Jonathan Isom’s I AM SOUL

Memphis Soul is a globally popular and widely recognizable brand of music and being-in-the-world. Created by the syncretic integration of West African rhythms, Mississippi Delta field hollers, blues music, and gospel riffs, Memphis Soul came of age in the urban and rural milieu of blues and racial repression from the plantations of Sunflower County to the juke joints of Beale Street. Soul, as a quality of being and an aesthetic, is quite literally at the root of every unique American artistic expression, from the collages of Romare Bearden and the choreography of Alvin Ailey, to the novels of Toni Morrison, to the expanses of hip-hop in the U.S. and beyond. And to be clear, Memphis has a premium on soul as an originary site of its spontaneous expression at the intersection of black urban and rural cultures by the Mighty Mississippi.

Structure Matters: “Orange Mound, Tennessee: America’s Community” and (Yet Another) Respectability Failure

My mother grew up at Midland and Boston in the Belt Line, a small working class subdivision in Orange Mound, in the 1950s and 1960s. Orange Mound is widely recognized as the nation’s first black neighborhood, and came into being when businessman Elzey Eugene Meachem bought the land from the Deadericks, who had run a sprawling plantation on the space. Meachem divided the land into plots and sold it to the city’s growing black population, pouring into Memphis from its rural surroundings in Mississippi, Arkansas, and Tennessee. Because of Orange Mound, and later, black communities in South Memphis and North Memphis, Memphis once boasted the largest percentage of black homeownership in the nation. (Because of unequal and racially discriminatory housing policies, the city posted some of the largest losses amongst black homeowners in the wake of the financial crisis in 2008. But I digress.) In Orange Mound, like in black communities across the country, residents created a strong sense of place that was rooted in racial uplift and the kind of general, if tenuous and fraught, mutual dependency that segregation necessitated.

Let the Politics of Respectability tell it, my mother came of age in the final two decades of “community” in the neighborhood, as integration would come along and devastate Orange Mound like it would do to other black neighborhoods. Presented with new opportunities for access to schools, resources, and services in new neighborhoods, middle classes moved out, the story goes, and left working classes and the poor to languish in a “culture of poverty” that included drug abuse, teen pregnancy, absent fathers, violence, gangs, sagging pants, dreadlocks, braids, gold teeth, HIV/AIDS, slang talk, booty shorts, and Love and Hip-Hop Atlanta. When these middle classes moved out, the working classes and poor folks left behind forgot how to take care of the outside of their homes, and broken windows, peeling paint, and crooked shutters abounded. Old folks were afraid in their homes as a black urban dystopian Clockwork Orange took over. When the children of the poor and working classes grew up, they either fled the neighborhood or were too disrespectful of the neighborhood’s history, or too cracked out, to cut the grass. And then babies were raising babies and grandmothers were 35 instead of 55. If only the men would take responsibility for their families, then men would be men, women would be women, and poor nigras would remember their place (behaving quietly and respectably and not embarrassing the black middle classes) again.

*Pause here for yawn.*

This narrative has been roundly critiqued, of course, not only for its logical fallacy but also for its inaccuracy. First, we know that the notion that all black folks across class lived right next door to and across the street from each other is simply wrong. Even within the strictures of a segregated society, black middle classes and elite carved out separate spaces within black neighborhoods and engaged in social and physical boundary work to demarcate those spaces and identities. This was especially true in the South, where more black people proportionally meant more black neighborhoods, which were differentiated, though subtly and certainly not completely, by status and wealth. And Orange Mound, like South Memphis, was comprised more of poor, working class, and what we might consider lower middle class blacks, than the relatively elite blacks of neighborhoods in North Memphis. Further, class, gender, and sexuality differences have always complicated black political organizing, and these complications were reflected in a host of institutional spaces, from churches to schools to neighborhoods. Integration merely allowed for a more definitive physical separation between classes.

Further, we know that black people across class adhered to what are today called middle class values. Again, this is especially true in the South, where a stronghold of evangelicalism and religiosity, combined with the rural rearing of most people who came to populate black southern city neighborhoods, yielded a sort of dogged conservatism that has rendered southerners unprepared for a host of changes from shifts in the global economy to public health threats like HIV/AIDS. Certainly folks lived outside of this rigid respectability plane–and those folks tended to be poor and working class and were the ones who created the blues and later rock n’ roll, jazz, and hip-hop. Yet, the rule of the day was respectability, which observed no class boundaries.

Third, we know that for all its pressed hems, closed legs, and mannerable tones, the politics of respectability ain’t never stopped, can’t never stop, and won’t never stop shit structural. It ain’t stop white folks from lynching scores of black people. It ain’t stop white men from raping scores of black women. It ain’t stop police brutality. It ain’t stop racial microaggressions. And verily I tell you it ain’t stop deindustrialization, the crack epidemic, mass incarceration, public education profiteering, changes in the welfare state that disproportionately disadvantaged black families, and that strategic disinvestment in the urban core known as urban renewal.

Unfortunately, some of the commentators in Emmanuel Amido’s new documentary, Orange Mound, Tennessee: America’s Community, would have us believe that pre-integration was a happier, less contentious time for black folks simply because of the compelled closeness of the time (rather than the significant structural shifts that happened in tandem with desegregation); that “values” are essentially a possession of the middle classes, and without their guiding presence after integration, poor and working classes forgot how to act; and that the politics of respectability could stop urban renewal and global deindustrialization.

Selected for competition screening at this year’s Indie Memphis film festival, Orange Mound, Tennesseee is a stirring portrait of the people of Orange Mound, of their memories of the tight-knit southern community of religiosity, respectability, and education that made Orange Mound the community it was, and of the commitment of the community’s residents to the neighborhood’s history, present, and future. It focuses on the memories of long-standing families in the neighborhood as well as neighborhood elites–the griots, the keepers of the neighborhood’s history. Taking us inside the storied Melrose High, the neighborhood school, we walk the halls with (now former) principal and Melrose graduate Leviticus Pointer as he endeavors to impart wisdom and order to students. We hear the Melrose choir singing classical and classically respectable Negro spirituals. We learn the history of the community, its significance and importance, and the sense of place older residents attach to the neighborhood.

Like I do with most things that shed light on a/the black southern experience, I want desperately to love this documentary.

However, Amido’s portrait is one that eschews actual structural analysis–facts, as it were–for the voices of people who are in some ways tragically incapable of telling a story that does not emphasize personal responsibility as the central causal factor for the neighborhood’s decline. Besides clips from a cartoon about an evil villain profiting from neighborhood decline (interesting in itself but poorly contextualized for the documentary) and saxophonist Kirk Whalum, who highlighted the role of Reagonomics and the importation of drugs into black communities as cause and context for the current state of Orange Mound and other such communities, structural chunks of the story were glaringly absent. This is largely a function of the sets of voices that are present and privileged in the narrative. Thus, despite the absolute essentialness and sheer beauty of the film, by relying too much on a narrow set of “experts” to theorize what he finds, Amido perpetuates the very stereotypes about inner-city neighborhoods and black people that he hopes to challenge.

Commentators in the film used phrases like “cycle of poverty” to talk about “babies having babies” with no indictment of the good southern churches in the neighborhood (and beyond) that refuse to engage in comprehensive sex education, that shame girls about their bodies and their desires, that take quiet pride in boys’ sexual prowess even if they in principle condemn their behavior, and the structures that cut young women off from access to reproductive health care. While there was handwringing over absent fathers, there was no discussion–NONE–of the prison industrial complex that profits from the incarceration of thousands of black and brown men, or of the changing structure of work that disadvantages the unskilled and working classes (and has done so since the 1960s), or of the ineffectualness of education to significantly improve poor people’s life chances, or of a shoddy physical and mental healthcare system that discriminates against people of color. “Permissive” parents (read: single mothers) were blamed for the state of the neighborhood without mention of deindustrialization, a discriminatory labor market, the prison industrial complex (and the misguided and unfair war on drugs that feeds it), or urban disinvestment.

To let the commentators tell the story, Orange Mound is not only racially segregated but is isolated from the effects of structure as well. At one point, a young white male visual artist who has moved into Orange Mound says that children of single parents are 70% more likely to have poor educational outcomes and live a life of crime. Beyond the fact that this is simply a boldface case of lying with statistics, I almost screamed at the screen, “DID YOU CONTROL FOR CLASS & EDUCATION DOE?!?!” (In case you’re wondering, the answer to that is, “of course he didn’t, because he’s a visual artist, and not a statistician.” Poor people are exposed to structural violence that disadvantages them and their children–violence not endemic to the state of single motherhood. Further, unlike white single mothers, few black mothers are raising children “alone” even if the child’s biological father is not involved at all. The same complex kin networks that made possible the imagined community of pre-integration also make possible childrearing networks. The problem is, as my colleague LaShawnDa Pittman argues, that these networks are now stretched far too thin as labor market changes allow less leeway for caring for ailing parents, small grandchildren, and oneself simultaneously with limited resources.) Amido offers nothing to contextualize, challenge, or simply correct these various assertions of “fact.” Consequently, fallacious and problematical opinions reign as gospel truth. Because these statements are presented as plausible, and because the only check on them is Whalum and the housing cartoon, we can only assume that Amido has uncritically accepted these explanations as well–which I hope and do not think is the case.

Watching the film in an audience of largely white folks save for a few black folks sprinkled here and there and a contingent of folks from Orange Mound who had participated in the documentary, I became increasingly irritated with the tired, trite explanations for neighborhood change. If we went into a white midwestern or southern town overcome by methamphetamine, would we say permissive parents and the absence of middle class values were the cause of the town’s woes? Should we allow people on the street with certain epistemological predispositions to explain Obamacare to the masses without context or correction? If Moynihan could have had a film accompaniment to his report, this documentary, driven by the classist Cosbyian respectability politics and astructural commentary of a few powerful voices (of baby boomer blacks), would have been a contender.

In addition to the documentary’s lack of structural context for the changes in black communities over time, the film also does not grapple with broader processes of urban change. Similar projects about neighborhoods endeavor more wholeheartedly to simultaneously present a structural narrative in concert with a “people” narrative, which this documentary should have done as well if it wants to make the bold claim that Orange Mound is “America’s community.” I certainly believe that Orange Mound is America’s community, and that there is an important story there to be told about history, race, region, class, culture, and neighborhood change from Reconstruction to Obama. However, the documentary may not incline viewers to take ownership of this community, since, to let some of the commentators tell it, it got itself into this mess.

America’s most vulnerable communities aren’t declining because of permissive parents and the absence of (middle class) “vallllllews.” City governments, in concert with realtors, lenders, other elite stakeholders, and sometimes the federal government, strategically disinvest in certain neighborhoods to create capital for the few with the latent consequence of further impoverishment or displacement for people in those neighborhoods. Public transportation in and out of these neighborhoods is underfunded and sometimes unreliable. Access to quality food and healthcare is scarce, which affects people’s ability to work, parent, and do a host of other things. (White) Homeowners and banks are often absent and irresponsible about property upkeep in black and poor neighborhoods where renters are a significant percentage of residents. Jobs are often a geographic and skills mismatch for the people who need them the most. Like other cities, we constantly lure companies here who pay few or no taxes and who pay our workers, the most vulnerable, the least. We won’t even fund quality education that will ensure that folks can do better because then how will we lure companies who want and need vulnerable workers that they can underpay and fatten their bottom lines with before they relocate to the global South? And then how will middle class (white) Memphians get kudos for sticking it out in a poor black city with big heart?

I will reserve comment on the young white suburban folks who are moving into the neighborhood to minister to people. Whalum says they’re not gentrifiers, but good people who really are operating from a place of love. Reserving. Comment.

I know that it might be difficult to engage in critical structural analysis, especially in a documentary like this one. However, Amido’s own admitted biases about inner-city neighborhoods are still on full display, despite the immense and genuine respect he has gained for the people of Orange Mound over the course of filming. When asked in the Q&A about the lack of structural analysis, he fumbled and launched the “cycle of poverty” play. When asked why the voices of these young folks who are supposedly responsible for neighborhood decline weren’t in the documentary, Amido replied that he had, in fact, interviewed them, but that they did not want to be featured in the film because many of them “are wanted.” (Sidenote: If I could get away with it, I might also tell someone that I didn’t completely trust that I had warrants to avoid appearing in a way I couldn’t control in a documentary.) His description of the circumstances they find themselves in–they’re incarcerated, they can’t get jobs, they turn to crime because they can’t get jobs, etc.–still doesn’t fully attend to structure. These men are more likely to be incarcerated for petty drug offenses because of the structure of racialized policing and a racist criminal justice system, which has nothing to do with permissive parents and values and everything to do with white supremacy. We know that black folks don’t even have to commit an actual crime to be swept up into the jaws of the criminal justice system. Just be in the wrong place. Or hell, be in the right place. Really, just be in your body.

The film suffers deeply from the absence of their voices. We get Negro spirituals–a respectable black expression–but no Melrose High School band, a clear and intergenerational centerpiece of the neighborhood’s identity. There are scores of rap songs repping Orange Mound (can you really make a documentary called Orange Mound, Tennessee and not play Eightball and MJG’s “Coming Out Hard,” like, throughout the entire soundtrack?), but nothing about the ways in which rap and hip-hop music continue the legacy of the neighborhood, deepen its sense of place, and extend its reach far beyond Memphis and the nation to the world. And there are ways to work in the perspectives of folks who don’t want to be on camera, especially if they hold such a crucial piece of the story. Without their voices, the documentary implicitly invites us–folks who aren’t their peers–to try them in absentia in Respectability Court.

As a stunning visual oral history of Orange Mound, Orange Mound, Tennessee: America’s Community works quite well, highlighting the voices of people who have lived through the neighborhood’s transition and their commitment to the community, despite the neighborhood’s change over time. The older residents featured in the film are hopeful about their community, if sometimes sad about the change, and we root for them as keepers of the legacy. Yet, as a comment on community change in America, and especially black community change, the documentary is an epic failure of respectability politics that presents a truncated history from the viewpoint of experts on respectability and personal responsibility. To understand what happened and what will happen in the future of the community, as Amido wants to do, a more careful and deliberate tangle with structural factors, as well as an engagement of the voices of young people, is essential.

This is the first of three reviews of films that screened at the 2013 Indie Memphis Festival. Click here for my review of Review of Susanna Vapnek’s Mabon Teenie Hodges: A Portrait of a Memphis Soul Original and Jonathan Isom’s I AM SOUL.

Riots and Rumors of Riots: Lessons from the University of Mississippi

On the night of the 2012 election, when Barack Obama was elected to a second term, some students at the University of Mississippi burned Obama campaign signs. They had procured these signs as they tore through the halls of dorms ripping them down. Under the cover of swiftness and invisibility, they moved through the halls gathering their loot while black students were captive and largely unaware inside their dorms.

The University’s public relations machinery, slumbering and oblivious—although inexplicably so, given that similar incidents took place when Obama was elected for the first time in 2008—scrambled to tamp down the emerging rumors and headlines.

The University’s silencing machinery of shade and spin had lacked its usual assassin-like precision, overtaken by the swift sprint of social media outlets, from Twitter to Facebook. A cell-phone quality picture of a circle of white male students burning an Obama sign accompanied every story and Facebook post. The papers said, “riot.” Equivocators said, “protest.”

The increasing popularity and facility of social media proved faster, swifter, than those feet running through halls snatching signs, faster even than the University’s infamously powerful PR spin. People were free to draw conclusions.

Well-intentioned whites, in pain, perhaps, for their black colleagues and friends, but burdened more by chagrin than outrage at inequality, quickly organized a candlelight vigil under the tenuous idea of “one Mississippi.” Scores of people raised candles outside of the same building where Meredith enrolled 50 years ago, escorted by armed guards, after a campus “riot”—or, if some prefer, “protest,”—left two people dead, dozens injured, and a state, a region, and a nation painfully aware of the vitriol and depth of white supremacy.

As I watched the events unfold on social media, my immediate reaction was one of sadness for the black students and colleagues I had befriended over my three years at the University of Mississippi. I was also sad for white colleagues who were powerless against the institution, despite their white privilege, and forced into silence and complicity with the institution’s mandate of white patriarchal supremacy.

I was neither shocked nor surprised by the events, as the University of Mississippi encourages this kind of behavior through its consistent inaction against a host of bad behaviors, from racial slurs scrawled in graffiti in dorm elevators to gross mishandling of cases of sexual harassment and rape. This institutional inaction is bolstered by the University’s identity as a bastion of the traditional, Old South: a white South where Dixie plays, confederate flags wave, and black people are subservient.

To be fair, the University has attempted to address these vestiges of a racist past. It stopped the band’s belting out of Dixie at football games and the flying of confederate flags, and has made overtures towards recruiting and retaining black faculty. Yet, as Faulkner instructs us, the past is not dead nor even past; we are haunted by these vestiges, as black women labor in the kitchens of white fraternity houses, “heritage not hate” dominates discussions of the South, and the wounds of the loss of the Northern War of Aggression are still oozing.

Thus, the University’s efforts to eradicate the past notwithstanding, Ole Miss’s identity as a place where men are men, women are women, and Nigras know their place is still functional for its enrollment and financial bottom line, attracting white students from all over the country and satiating powerful (but invisible) white alumni and big donors.

Although my training as a sociologist taught me well the workings of institutional power, at the University of Mississippi, I received an education by fire. I met black faculty so traumatized by their experiences there that they had either sublimated rage for the purposes of survival or been consumed by the rage to the point of intellectual and emotional paralysis.

I met worried white colleagues, fearful of if or when one of us would erupt, knowing we would be cast as privately troubled individuals, rather than symptomatic of a public problem.

I met oblivious white faculty.

I met white faculty saviors, eager to solve the problem and save the day, even at the expense of alienating black colleagues. I met underpaid staff called into work when their babies were sick, who had to come lest they risk their pittance and their jobs.

I met black students consumed by the most terrible pathologies, whose quest to belong and disbelieve the University’s history and identity led them to defend the institution fervently.

I met black students unaware of the trauma the institution was enacting upon them. I met black students who were painfully aware of that trauma, who were in pain because of it, but who determined to do as much as they could within their limited powers.

Meanwhile, the official message was that the University of Mississippi was one of the best places to work with one of the most beautiful campuses. Oxford is a wonderful town. The University is committed to recruiting and retaining diverse faculty.

The first black student body president is elected. The University hosts a presidential debate. The University remembers Meredith’s sacrifice. The first black teacher of the year is selected. The University is committed to fairness. The University will not tolerate discrimination. The first black homecoming queen is elected. The University commemorates the Civil Rights Movement. The University acknowledges that it still has a ways to go, but has nonetheless come a long way.

See Jane run. Jane is fast. But she cannot outrun white supremacy.

Over my time at the University of Mississippi, and in particular in the second two years, I became physically and psychologically ill. I knew something was wrong when, in response to a student’s angry question of why “Mexicans” should not have to learn English, I laughed hysterically and uncontrollably for two minutes. I was co-teaching the course, and thankfully, my interlocutor was able to take over until I calmed down.

When I felt a strong urge to be physically violent with a student who sent a threatening email and angrily paced outside of my office to confront me about comments on a paper—comments that I had not, in fact, written, but that had been written by my colleague—I knew something was wrong.

I had angry outbursts and crying spells. I ate to keep from shouting and crying. I gained 30 pounds. I developed a serious kidney infection because I would pathologically drive the 30 miles to Batesville—the first major town on my way home to Memphis—to use a gas station bathroom rather than linger a minute on the University of Mississippi’s campus or in Oxford to relieve myself after a long day at work.

I developed a baseball-sized, rock-hard cyst in my breast. I continued to dissemble, though. I worked with students, attended meetings, and wrote. But I had been overtaken and lapped by white supremacy.

The climate at the University of Mississippi reflects the broader mood and character of whiteness and thus is instructive in its ability to signal power’s next moves. Someone must be punished for tarnishing the University’s image in an historic year—the commemoration of Meredith, integration, and Civil Rights—and a few white students will be trotted out and sacrificed to meet this demand. Perhaps some black students, too, will be punished for reverse rioting/protesting.

The institution will shore up its public relations machinery; surely, someone will be appointed to always be on call to respond to these kinds of incidents. But the institution, like whiteness, will not change. It will not turn inward. It will not reflect. That is not the nature of institutions.

Further, the climate at the University of Mississippi reflects the climate at many institutions, academic and corporate. My experience, in this respect, is not unique. Faculty of color at a number of institutions are marginalized and under assault from institutions that benefit tremendously from their presence but cannot seem to invest reciprocally in their success as faculty and health as people. This contributes to stagnant numbers of faculty of color overall, even as recruitment of faculty of color increases.

Faculty of color not only move about between institutions, but also exit the academic field entirely, opting to start non-profits, small businesses, and other ventures where they can exercise more autonomy and limit their experiences of racial microaggressions.

Still, as institutions like the University of Mississippi continue to focus on recruitment, rather than on fundamentally changing campus climates, the face of administration, and practices that disadvantage and discourage faculty of color (and indeed most faculty who are not single white men), little will be done to ease the exodus of people of color.

Yet, institutions can and do move, albeit it slowly, especially in response to external threats. The Republican Party, for instance, trounced by “demographics”—media code for people of color, women, LGBT persons, and progressive urbanites—can be a formidable force in 2016 by basing their campaign strategy not on overt white patriarchal supremacy, but rather benign white patriarchal supremacy, especially that cloaked in the colored faces of Bobby Jindal and Marco Rubio.

If it is to continue to be the Demographic Party, the Democratic Party will need to effect real change on issues of sustainability and equality rather than teetering on in its typical center-right, neoliberal fashion. A third party, as a new(-er) institution, could capitalize handily on government intractability, people’s dissatisfaction, and grassroots momentum to envision possibilities for a more equitable, responsible, and sustainable nation-state.

As faculty of color, we have a responsibility to advocate for all students, and a disproportionate responsibility to champion marginalized students, including students with disabilities, students of color, and LGBT students. We have an obligation to University staff of color, who labor alongside us often without our relative privilege and autonomy. We also, as long as we are in them, have a responsibility to institutions—even when they do not behave responsibly—to demonstrate the importance of change and offer our distinct insights. If we all push, the institution may move a centimeter.

The University of Mississippi reinforced for me that classic sociological lesson about the rigidity of institutions. It also reaffirmed my commitment to and investment in research, teaching, mentoring, and even (certain kinds of) service.

I built lifelong friendships with students, faculty, and staff there, important relationships that have shaped my scholarship and my approach to my academic work. Perhaps most importantly, it taught me that I must care for myself. After all, if I drop dead with an acute case of allergic white supremacitis, the institution will continue on in all of its glorious inertia.

*This essay was originally published in the November 2012 edition of the Association of Black Sociologists Newsletter, The Griot.

“Givin Em What They Love”: Janelle Monáe and the Sonic Aesthetics of Black Womanhood

An early and relatively comprehensive review of Electric Lady essentially praised the album and the artist for gumption but criticized what might be called the album’s sonic “extraness” and the supposed disconnect between the album’s sounds and its concepts. Jody Rosen argues that, “in several of The Electric Lady’s nineteen songs, Monáe keeps adding ingredients—key changes, counter-melodies, guitar solos, orchestral flourishes—in a way that feels willful. The songs wear you down; sometimes they grow downright dull.”

To put the “you’re a virgin…who can’t drive” stank on it, Rosen says:

“The rococo embellishments, the ‘electric overtures’ (there are two of them here), the grandiose thematic overlay: It all feels like a reach, an attempt to jump a rocket ship to Planet Genius. That’s a move, her friend Prince could tell her, that’s best left until, say, your fourth album — or at least until you’ve refined your craft and chops. Monáe’s need work. Her songwriting remains fuzzy; her singing voice is serviceable but light, lacking flavor and bite.”

That was way harsh, Tai.

As a classically-trained violinist who started Suzuki lessons at age 3 and a general student and lover of music, I cannot fundamentally, wholeheartedly, and unabashedly disagree with Rosen as I so *desperately* want. But as a black woman and a black feminist with womanist roots straddling third and fourth waves of black feminist work? I can totally offer a resounding HELL NAW to these assessments.

On Electric Lady, art, aesthetics, sound, politics, and black women’s lived experience exist indistinguishable from one another on the same exact plane. That is, Janelle Monáe’s art isn’t catching up to her/the ideas; the ideas are the art, the masterpiece. True, the central idea she’s trying to get across—black women are complex human beings—might be extraordinarily complicated for some people to get, given that black women are inhabited, colonized, and worn to work by white supremacy every day all over the globe. As such, it takes a great number of rhetorical devices, from science fiction to simile, as well as flourishes, booms, bangs, and horn section solos, to articulate black women’s ontology in a social landscape that cannot even imagine the possibility of such a thing existing. But as a black woman, Janelle Monáe is quite accustomed to attempting to explain things to people who are not predisposed to understand. Thus, she heaps on the sound and the metaphor to help the confused, handing out a cheatsheet, as it were, for Seeing Black Women As Human When You’d Rather See Them As Big-Bootied Welfare Queens/Hoes/Sluts.

But Electric Lady is not intended to be an explanatory handbook for those who cannot recognize, in the existential sense, black women. While J. Monáe pauses to look back to the larger audience here and there, she is largely conducting an in-group conversation. Black women are the central, past, present, and future subjects of the album, and their voices and experiences are varied: from the “ghetto woman” making a way out of no way in underpaid employment; to the brickhouse-body dimes “tall like a ceiling/wearing fancy things”; to the bright and shiny sorority droids Melanie 45221 and Assata 8550 who announce the bouncing electrobooty contest; to the ever-elusive Everywoman savior Cindi Mayweather; to the “bitches who love to rock and roll” to the “bands that make them dance apocalyptic” to the “Q.U.E.E.Ns” who fundamentally reject the politics of respectability and whose booties don’t lie; to the electric ladies shocking it and breaking it; to the women with the hypnotic, or Dorothy Dandridge eyes, with which they create works of art; to the sleeping Mary being awakened to the fact that she “got the right to choose”; to Sally, riding, and gone, even though we love her. Black women are the “preachers and teachers” on the Electric Lady,beings who are and speak and love and who have lived experiences that should be known, respected, and understood. They are not, the album implicitly and sometimes explicitly asserts, caricatures or suits to be taken on and off by Miley Cyrus. Even though there’s a seeming Matrix-like dichotomy of options for electric ladies, “sleeping” or “preaching,” the album also implies that as corporeal testaments to the continued disenfranchisement of the marginalized, black women’s rule-breaking booties and bodies are always already preaching about justice.

And where black women are the subjects, writing their own stories, singing in the fullness of all of their voices, there is much love. There is a soul love for the people, intimate partner love, agape and erotic adoration for all of the electric ladies, erotic love, “undercover” love, love for the hardworking women, love for the women with their skirts on the ground, deep, strong, love, a love that can be felt all over. This love is a fundamental experience that makes her want “to scream and dream and throw a love parade.” (With permission, of course: “is that okay?”) There is an abundance of love here, despite the impending apocalypse and the evil robot overlords. That love can exist where there is destruction is a feat that only black women can pull off with such resolve. The album sounds like love, too. From the gliding, sliding, glissandi strings in the opening Electric Overture to the La-ah-ah-ah-ahs at the end of “What an Experience,” J. Monáe builds a sonic aesthetic of black women’s being-as-love through this sonic extraness. This kind of soundscape demands counter-melodies, strong fifths, pounding basslines, brassy brass sections, all layered on top of one another, to capture the complexity of black women’s ontology with the hopes that untrained listeners will catch a bit of it and moreover that black women will be affirmed by and hear themselves in it. In short, J. Monáe’s sound shouts and “feels willful” because this is the only way to engage with constant negation.

To be sure, the album as a whole is a black feminist/womanist Afro-futurist, Afropunk manifesto. Yet, J. Monáe manages to fit a significant chunk of black women’s ontology into the four minutes and twenty-six seconds of “Givin Em What They Love.” The song, the first track after the album-opening Electric Overture, offers a statement about black womanhood and black women’s relationship to the world—as givers of what people love, even if those folks’ love for what we give is rabid, exploitative and pathological. Instead of advocating for a politics of respectability-style cloaking of that which might be loved by the (white/male) Other, J. Monáe declares that we should/ought to outright give em what they love. At once a rallying cry, liberation chant, and redemption song, the lyrics are absolutely audacious: “I am sharper than a razor/eyes made of lasers/bolder than the truth,” and “I ain’t neva been afraid to die/look a man in the eye.” She is. She ain’t. She does. Those kind of lyrics coming from a young black woman with working class roots (in a context where even the nation’s first lady is subject to racialized and gendered stereotypes and policing) require a complementary sonic audacity.

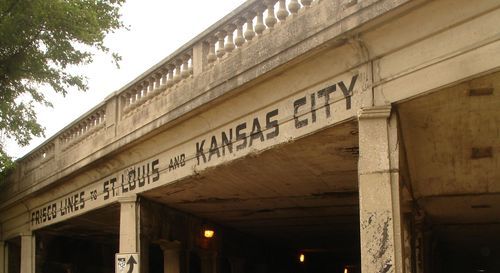

“Givin Em What They Love” begins with a chain gang hammering the stakes into the Frisco train line from “Kansas to New Atlantis,” Or Memphis to Kansas. Or Kansas to Los Angeles. The universality of the “sound of the men/working on the chain gang” collapses place distinctions in service of a multi-located (temporally and spatially) blackness and black feminist ontology. The bass line is both steady and sure, punctuated on the second and up beats by a martellato drum accent that can only be the hammers, many echoing in unison, of the chain gang. When J. Monáe enters as lead singer and conductor, her voice rests on and hovers over this basic foundation. She both disciplines and is disciplined by the bass line.

The downbeat is often purposely empty, a pause in the rhythm to showcase the upbeat and the second beat. Playing on the two and four is not the straightforward message of funk, which often brings the message and beat in on the first. J. Monáe opts not to hit people over the head as soon as they come in the room, giving instead a rock-inspired soul sound with the message and emphasis on the two. She continues to skirt the downbeat in most measures, as does the bass line and drum. In fact, the chorus is the first time in the song the downbeat is hit directly and forcefully with the beginning of a phrase. And what message comes on the downbeat for black women? A one-worded one: “LOVE.” Prince, as background singer and voice of the chain gang laboring for and with J. Monáe, belts it out in fifths for a full measure and a beat and a half. And when homegirl preaches, she preaches on the downbeat. The Baptist church organs that precede the bridge signal the congregation to get ready for her message. Invariably, it is a message of about how to love:

TAKE your time/take what you love baby/JUST enough/but never too much baby/TAKE your time/take what you love and when that/BAYby cries you betta look at that baby/TAKE your time/take what you love baby/JUST enough/but never too much baby/TAKE your time/when you give me some love

*Pause here to take love notes.*

And then after she has preached the lesson, she wails love over the guitar solo. Which is over the chorus. Which is over the organ. Which is over the bass guitar. Which is over the snare and bass drum. Taken together, this is the sound of a/the multilayered black feminist ontology that we are being prepared to receive on the rest of the album. Then, to further articulate the complexity of black womanhood, a horn feature comes in that my soul needs to hear Jackson State University’s Sonic Boom or Southern University’s Jukebox play post haste. (Talk about bands that make me dance apocalyptic.) And like an HBCU band, the horns hit every. single. beat. The song’s denouement allows the organ, horns, guitar, and eventually J. Monáe’s voice to be replaced by the rich legato of a string quintet and the echo of the Prince-voiced chain gang Greek chorus, which has been echoing J. Monáe: “undercover love/…wearing fancy things…/oh, we didn’t know what to do…/tell me where the party at…” The song’s sonic audacity encapsulates a black womanhood fiercely struggling against erasure while also embracing, teaching about, and giving love. That takes a lot of organs and drums and guitars and strings and horns. And maybe some harpsichord. (Okay. So maybe the harpsichord would be extra. Or maybe not.)

Electric Lady is indeed ambitious, as is any endeavor to capture a marginalized group’s being-in-the-world, especially through art. And yes, its multiple influences and significations are at times dizzying. But, this multilayered sonic extraness is exactly the frequency on which black womanhood necessarily operates. It’s the frequency on which others may at least begin to hear black womanhood. And moreover, it’s the frequency on which black women can reflect on themselves and see and hear themselves reflected as they are. For that reason, I’m staying tuned.