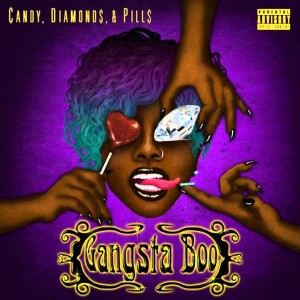

Gangsta Boo’s Enquiring Minds (1998) was the soundtrack to a season of fence-jumping feminism, a culmination of springs, summers, and falls spent fighting boys and finding our voices in communities that worked to silence the raucous and bulbous female parts of us. We had been anticipating the album, knowing full well Lola Mitchell’s refusal to be tucked and secreted, and also anxious about our need for her voice to confirm the black southern girl theory we conjured every day beyond boys’ earshot. [Read more…]

Gangsta Boo’s Enquiring Minds (1998) was the soundtrack to a season of fence-jumping feminism, a culmination of springs, summers, and falls spent fighting boys and finding our voices in communities that worked to silence the raucous and bulbous female parts of us. We had been anticipating the album, knowing full well Lola Mitchell’s refusal to be tucked and secreted, and also anxious about our need for her voice to confirm the black southern girl theory we conjured every day beyond boys’ earshot. [Read more…]

“An Idea of Change”: Marco Pavé and the Politicization of Memphis Hip-Hop

Art is always already personal and political. Memphis native Marco Pavé’s recently released mixtape, Obscure Reality, and his community work in and beyond his neighborhood, exemplify this dual function of art, as well as the possibilities of art to reflect and instigate social change. The 21-year-old rapper operates squarely in the tradition of Memphis hip-hop artists before him, who have frequently used their work to tell untold stories, reckon with the ghosts of King and civil rights, and highlight the city’s current social position. Yet, as part of the center of a bourgeoning movement of young creatives and intellectuals speaking back to the city’s unequal power relationships, Pavé marshals his art for direct action and transformation of his neighborhood and city. [Read more…]

Art is always already personal and political. Memphis native Marco Pavé’s recently released mixtape, Obscure Reality, and his community work in and beyond his neighborhood, exemplify this dual function of art, as well as the possibilities of art to reflect and instigate social change. The 21-year-old rapper operates squarely in the tradition of Memphis hip-hop artists before him, who have frequently used their work to tell untold stories, reckon with the ghosts of King and civil rights, and highlight the city’s current social position. Yet, as part of the center of a bourgeoning movement of young creatives and intellectuals speaking back to the city’s unequal power relationships, Pavé marshals his art for direct action and transformation of his neighborhood and city. [Read more…]

Mississippi Prometheus: Big K.R.I.T. and The Southern Black/Rap Snapback

May 21, 2014

Awnaw, hell naw, mane, y’all done up and done it/…them country boys on the rise – Nappy Roots, “Awnaw”

Stop being rapper racists/region haters/…This is southern face it/if we too simple/then y’all don’t get the basics – Lil’ Wayne, “Shooter”

Hope the hook wasn’t too simple/either way, nigga, I wrote it/yes, I made the beat/yes, I made the track…I don’t fall in line/I define what’s rhyme – Big K.R.I.T., “Mt. Olympus”*

“I swear a country nigga snap…” – Big K.R.I.T., “Mt. Olympus”

While “country” is oft-times a pejorative term meant to denote someone’s greenness, lack of sophistication, or backwardness, black southerners have long used country to describe an existence rooted in dirt and power, and the ability to survive and maneuver through a world that would rather them not. Still, in its use as an insult, “country” reflects black Americans’ discomfort with southern blackness and its linkages to historical anxieties about the trauma of slavery, black male emasculation, the dehumanizing violence of Jim Crow, and the continued anti-modernity of the (rural) South. Whether the players are Richard Wright and Zora Neale Hurston, Spike Lee and Tyler Perry, or Ice-T and Soulja Boy, as I argue in This Ain’t Chicago, in the aggregate drama of black representation, black folks would rather excise all country niggas–who are seen as reminders of a past of subjugation–from the narrative of the race.

Drake Plays the Blues: “Down South” and the Black Imaginary in “Worst Behavior”

December 31, 2013

http://vimeo.com/79018443

“Down South” is a ubiquitous trope in the black American imagination, used to conjure actual and fictive remembrances of a space and time removed from and outside of modernity, the anti-present. It’s an imagined space through which one, usually a seasonal migrator or former southerner, or an altogether non-southerner, can safely navigate a number of complexities of personal history, home, memory, and angst. With the 10-minute video for “Worst Behavior” Drake uses the notion of Down South, and Memphis in particular, to narrate broader ideas about authenticity, masculinity, fatherhood, home, and longing.

man, muhfuckas neva loved us

Cash Money Records afforded Aubrey Drake Graham, the middle class biracial Jewish Canadian kid of Degrassi fame, a black audience and black working class authenticity through proximity to some New Orleans hot boys. This proximity, along with his rap prowess, has afforded Drake some space to blossom in a game that seemed to not yet have room for him. Still, jokes about Drake abound, with the rapper frequently making the problematical Top 10 Softest Rappers in the Game list and an infamous meme about his Dada outfit circulating through the interwebs in summer 2013. Further, Cash Money has not completely eradicated the artist’s authenticity troubles. Grumbles about “Started from the Bottom”–how dare a middle class Canadian kid talk about starting from the bottom?–revealed the intraracial class dynamics of the prerequisites for authenticity. That is, one might now be extraordinarily wealthy, but as long as she or he started from a legible bottom–say, the Hollygrove neighborhood of New Orleans–one can enjoy unlimited authenticity, no matter how pop one becomes.

“Playing on the One”: Memphis Soul from Teenie Hodges to Tonya Dyson

November 15, 2013

Review of Susanna Vapnek’s Mabon Teenie Hodges: A Portrait of a Memphis Soul Original and Jonathan Isom’s I AM SOUL

Memphis Soul is a globally popular and widely recognizable brand of music and being-in-the-world. Created by the syncretic integration of West African rhythms, Mississippi Delta field hollers, blues music, and gospel riffs, Memphis Soul came of age in the urban and rural milieu of blues and racial repression from the plantations of Sunflower County to the juke joints of Beale Street. Soul, as a quality of being and an aesthetic, is quite literally at the root of every unique American artistic expression, from the collages of Romare Bearden and the choreography of Alvin Ailey, to the novels of Toni Morrison, to the expanses of hip-hop in the U.S. and beyond. And to be clear, Memphis has a premium on soul as an originary site of its spontaneous expression at the intersection of black urban and rural cultures by the Mighty Mississippi.

“Givin Em What They Love”: Janelle Monáe and the Sonic Aesthetics of Black Womanhood

An early and relatively comprehensive review of Electric Lady essentially praised the album and the artist for gumption but criticized what might be called the album’s sonic “extraness” and the supposed disconnect between the album’s sounds and its concepts. Jody Rosen argues that, “in several of The Electric Lady’s nineteen songs, Monáe keeps adding ingredients—key changes, counter-melodies, guitar solos, orchestral flourishes—in a way that feels willful. The songs wear you down; sometimes they grow downright dull.”

To put the “you’re a virgin…who can’t drive” stank on it, Rosen says:

“The rococo embellishments, the ‘electric overtures’ (there are two of them here), the grandiose thematic overlay: It all feels like a reach, an attempt to jump a rocket ship to Planet Genius. That’s a move, her friend Prince could tell her, that’s best left until, say, your fourth album — or at least until you’ve refined your craft and chops. Monáe’s need work. Her songwriting remains fuzzy; her singing voice is serviceable but light, lacking flavor and bite.”

That was way harsh, Tai.

As a classically-trained violinist who started Suzuki lessons at age 3 and a general student and lover of music, I cannot fundamentally, wholeheartedly, and unabashedly disagree with Rosen as I so *desperately* want. But as a black woman and a black feminist with womanist roots straddling third and fourth waves of black feminist work? I can totally offer a resounding HELL NAW to these assessments.

On Electric Lady, art, aesthetics, sound, politics, and black women’s lived experience exist indistinguishable from one another on the same exact plane. That is, Janelle Monáe’s art isn’t catching up to her/the ideas; the ideas are the art, the masterpiece. True, the central idea she’s trying to get across—black women are complex human beings—might be extraordinarily complicated for some people to get, given that black women are inhabited, colonized, and worn to work by white supremacy every day all over the globe. As such, it takes a great number of rhetorical devices, from science fiction to simile, as well as flourishes, booms, bangs, and horn section solos, to articulate black women’s ontology in a social landscape that cannot even imagine the possibility of such a thing existing. But as a black woman, Janelle Monáe is quite accustomed to attempting to explain things to people who are not predisposed to understand. Thus, she heaps on the sound and the metaphor to help the confused, handing out a cheatsheet, as it were, for Seeing Black Women As Human When You’d Rather See Them As Big-Bootied Welfare Queens/Hoes/Sluts.

But Electric Lady is not intended to be an explanatory handbook for those who cannot recognize, in the existential sense, black women. While J. Monáe pauses to look back to the larger audience here and there, she is largely conducting an in-group conversation. Black women are the central, past, present, and future subjects of the album, and their voices and experiences are varied: from the “ghetto woman” making a way out of no way in underpaid employment; to the brickhouse-body dimes “tall like a ceiling/wearing fancy things”; to the bright and shiny sorority droids Melanie 45221 and Assata 8550 who announce the bouncing electrobooty contest; to the ever-elusive Everywoman savior Cindi Mayweather; to the “bitches who love to rock and roll” to the “bands that make them dance apocalyptic” to the “Q.U.E.E.Ns” who fundamentally reject the politics of respectability and whose booties don’t lie; to the electric ladies shocking it and breaking it; to the women with the hypnotic, or Dorothy Dandridge eyes, with which they create works of art; to the sleeping Mary being awakened to the fact that she “got the right to choose”; to Sally, riding, and gone, even though we love her. Black women are the “preachers and teachers” on the Electric Lady,beings who are and speak and love and who have lived experiences that should be known, respected, and understood. They are not, the album implicitly and sometimes explicitly asserts, caricatures or suits to be taken on and off by Miley Cyrus. Even though there’s a seeming Matrix-like dichotomy of options for electric ladies, “sleeping” or “preaching,” the album also implies that as corporeal testaments to the continued disenfranchisement of the marginalized, black women’s rule-breaking booties and bodies are always already preaching about justice.

And where black women are the subjects, writing their own stories, singing in the fullness of all of their voices, there is much love. There is a soul love for the people, intimate partner love, agape and erotic adoration for all of the electric ladies, erotic love, “undercover” love, love for the hardworking women, love for the women with their skirts on the ground, deep, strong, love, a love that can be felt all over. This love is a fundamental experience that makes her want “to scream and dream and throw a love parade.” (With permission, of course: “is that okay?”) There is an abundance of love here, despite the impending apocalypse and the evil robot overlords. That love can exist where there is destruction is a feat that only black women can pull off with such resolve. The album sounds like love, too. From the gliding, sliding, glissandi strings in the opening Electric Overture to the La-ah-ah-ah-ahs at the end of “What an Experience,” J. Monáe builds a sonic aesthetic of black women’s being-as-love through this sonic extraness. This kind of soundscape demands counter-melodies, strong fifths, pounding basslines, brassy brass sections, all layered on top of one another, to capture the complexity of black women’s ontology with the hopes that untrained listeners will catch a bit of it and moreover that black women will be affirmed by and hear themselves in it. In short, J. Monáe’s sound shouts and “feels willful” because this is the only way to engage with constant negation.

To be sure, the album as a whole is a black feminist/womanist Afro-futurist, Afropunk manifesto. Yet, J. Monáe manages to fit a significant chunk of black women’s ontology into the four minutes and twenty-six seconds of “Givin Em What They Love.” The song, the first track after the album-opening Electric Overture, offers a statement about black womanhood and black women’s relationship to the world—as givers of what people love, even if those folks’ love for what we give is rabid, exploitative and pathological. Instead of advocating for a politics of respectability-style cloaking of that which might be loved by the (white/male) Other, J. Monáe declares that we should/ought to outright give em what they love. At once a rallying cry, liberation chant, and redemption song, the lyrics are absolutely audacious: “I am sharper than a razor/eyes made of lasers/bolder than the truth,” and “I ain’t neva been afraid to die/look a man in the eye.” She is. She ain’t. She does. Those kind of lyrics coming from a young black woman with working class roots (in a context where even the nation’s first lady is subject to racialized and gendered stereotypes and policing) require a complementary sonic audacity.

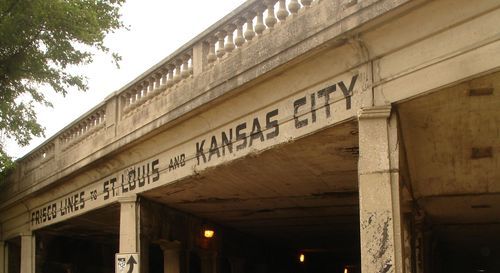

“Givin Em What They Love” begins with a chain gang hammering the stakes into the Frisco train line from “Kansas to New Atlantis,” Or Memphis to Kansas. Or Kansas to Los Angeles. The universality of the “sound of the men/working on the chain gang” collapses place distinctions in service of a multi-located (temporally and spatially) blackness and black feminist ontology. The bass line is both steady and sure, punctuated on the second and up beats by a martellato drum accent that can only be the hammers, many echoing in unison, of the chain gang. When J. Monáe enters as lead singer and conductor, her voice rests on and hovers over this basic foundation. She both disciplines and is disciplined by the bass line.

The downbeat is often purposely empty, a pause in the rhythm to showcase the upbeat and the second beat. Playing on the two and four is not the straightforward message of funk, which often brings the message and beat in on the first. J. Monáe opts not to hit people over the head as soon as they come in the room, giving instead a rock-inspired soul sound with the message and emphasis on the two. She continues to skirt the downbeat in most measures, as does the bass line and drum. In fact, the chorus is the first time in the song the downbeat is hit directly and forcefully with the beginning of a phrase. And what message comes on the downbeat for black women? A one-worded one: “LOVE.” Prince, as background singer and voice of the chain gang laboring for and with J. Monáe, belts it out in fifths for a full measure and a beat and a half. And when homegirl preaches, she preaches on the downbeat. The Baptist church organs that precede the bridge signal the congregation to get ready for her message. Invariably, it is a message of about how to love:

TAKE your time/take what you love baby/JUST enough/but never too much baby/TAKE your time/take what you love and when that/BAYby cries you betta look at that baby/TAKE your time/take what you love baby/JUST enough/but never too much baby/TAKE your time/when you give me some love

*Pause here to take love notes.*

And then after she has preached the lesson, she wails love over the guitar solo. Which is over the chorus. Which is over the organ. Which is over the bass guitar. Which is over the snare and bass drum. Taken together, this is the sound of a/the multilayered black feminist ontology that we are being prepared to receive on the rest of the album. Then, to further articulate the complexity of black womanhood, a horn feature comes in that my soul needs to hear Jackson State University’s Sonic Boom or Southern University’s Jukebox play post haste. (Talk about bands that make me dance apocalyptic.) And like an HBCU band, the horns hit every. single. beat. The song’s denouement allows the organ, horns, guitar, and eventually J. Monáe’s voice to be replaced by the rich legato of a string quintet and the echo of the Prince-voiced chain gang Greek chorus, which has been echoing J. Monáe: “undercover love/…wearing fancy things…/oh, we didn’t know what to do…/tell me where the party at…” The song’s sonic audacity encapsulates a black womanhood fiercely struggling against erasure while also embracing, teaching about, and giving love. That takes a lot of organs and drums and guitars and strings and horns. And maybe some harpsichord. (Okay. So maybe the harpsichord would be extra. Or maybe not.)

Electric Lady is indeed ambitious, as is any endeavor to capture a marginalized group’s being-in-the-world, especially through art. And yes, its multiple influences and significations are at times dizzying. But, this multilayered sonic extraness is exactly the frequency on which black womanhood necessarily operates. It’s the frequency on which others may at least begin to hear black womanhood. And moreover, it’s the frequency on which black women can reflect on themselves and see and hear themselves reflected as they are. For that reason, I’m staying tuned.