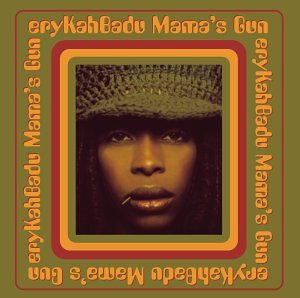

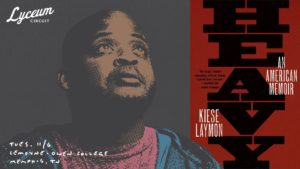

This fall I did a series of calls to students in my “The ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture” and Blackness and Digital Life courses. I did a call almost every week until my body wouldn’t allow me to do so anymore. I recorded them in one take, so there are imperfections in them all. I was doing the best I could. Lectures such as these served as the call, and then selected students would offer an in-depth response, and then the rest of the class would constitute the choir, singing on the themes for that particular week. After the call, response, and choir, we would convene synchronously to discuss. All of this was happening in the digital spaces of Canvas message boards and Google Docs and Zoom. This is one such lecture for “The ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture.” The previous week we had read Raquel Gates’ Double Negative. For this week, we read selections from Elizabeth Alexander’s The Black Interior, the entirety of Kevin Quashie’s The Sovereignty of Quiet, and students could choose Barry Jenkins’ Medicine for Melancholy or Moonlight to watch. You can listen/watch here.