24 Feb 2014

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately…” -Thoreau, 1854

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” -Faulkner, 1950

“And I can feel it for sure/I been here before.” -Teena Marie, 1979

“I guess I’ll see you next lifetime/I’m gone be there.” – Erykah Badu, 1997

“I’m going live (forever and ever and ever) from the underground.” – Big K.R.I.T., 2013

The mathematics of what this is and is not: review < musing.

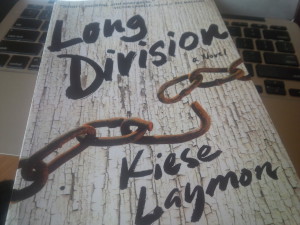

One time I was in a philosophy dissertation defense about Levinas, and one of the philosophy professors in attendance asked the defending candidate, “If I were walking down the street, how would I know transubstantiation when I saw it?” The candidate’s answer was, “I’m not sure that you would, but you just would.” Some folks thought it was an absurd question for various reasons, and still others thought the answer was absurd for various reasons, but I understood then, and was reminded of the exchange many times reading Kiese Laymon’s Long Division. Reading it is like watching your ontology walk past you on the street like déjà vu and pointing at it gaped-mouthed and speechless, trying to name it because you know it, but you can’t because it’s way bigger than you are, even though it is, in fact, only little ol’ you walking by. Reading it does this to you because the book is like the blues, traveling easy across time, sometimes on the downbeat, but usually on the 2 & 4, and sometimes in between.

One time I was in a philosophy dissertation defense about Levinas, and one of the philosophy professors in attendance asked the defending candidate, “If I were walking down the street, how would I know transubstantiation when I saw it?” The candidate’s answer was, “I’m not sure that you would, but you just would.” Some folks thought it was an absurd question for various reasons, and still others thought the answer was absurd for various reasons, but I understood then, and was reminded of the exchange many times reading Kiese Laymon’s Long Division. Reading it is like watching your ontology walk past you on the street like déjà vu and pointing at it gaped-mouthed and speechless, trying to name it because you know it, but you can’t because it’s way bigger than you are, even though it is, in fact, only little ol’ you walking by. Reading it does this to you because the book is like the blues, traveling easy across time, sometimes on the downbeat, but usually on the 2 & 4, and sometimes in between.

I thought after the third reading of Long Division I’d be qualified to speak on it, but I still ain’t, so this is less a review, more a musing on the thing. For almost nine months, I’ve avoided most discussions and reviews of the text, other than Laymon’s own, like TV show fans avoid spoiler alerts. For a black southern reader, Long Division requires some quiet reckoning with one’s interiority as well as some raucous, in-your-face group discussions, which can but usually cannot happen on the Internet. Yet, I can say with absolute certainty that Long Division has, in one text and with some of the trillest sentences ever, answered the call of southern hip-hop and black southern film to have more voices at the table singing out about who we are across space, place, and time. For a people, a place, and spaces, who, as André 3000 instructs us, got something to say, Long Division claps, bangs, raps, and speaks loud in the darkness, such that the message reverberates through the now, the past, and the future in the civil rights, rural, urban, contemporary, Katrina, Gulf Coast, and Melahatchie Souths.

Even though we make overtures to the intersection of time and space, in practice, temporality and geography are usually considered separately. In Long Division, though, time, space, and place converge as characters, plot devices, words, paragraphs, and ellipses. Seriously considering time and space together requires a bold affirmation of and careful attention to people and places, and Laymon offers that for black southerners and/in the South. The novel is haunted, in fact, by time and space, as the past is and interrupts the characters perpetually as they strive to write and change their futures. The three temporal Souths in Long Division coincide with the civil rights South, the crack South, and the post-Katrina South, which are simultaneously times and spaces and places. These moments are each apt representations of moments of space/time rupture—where Jackson, Glendora, Birmingham, and Highway 51 ran smack into each other; where crack and your cousin from Chicago who was “in a gang” and weapons and cats with one red Fila and one black British Knight on ran smack into Clarksdale, Little Rock, and Biloxi; where oil and orchestrated disaster and race and region and religion and rurality ran smack into the Gulf Coast and the lower ninth ward. With Chicago looming in the backdrop as a distant urban space that is/was and is/was not the South, we are invited to time travel, to traverse these Souths, the rural, urban, and small-town Souths. We are encouraged to think about the piney woods with all of their questions and answers; Melahatchie and Jackson; the Mississippi Gulf Coast and New Orleans. But from civil rights to crack to Katrina, we can move back and forth through time and end up in the same place and space because the structures are the same. Yet, Laymon’s narrative rejects this fixed outcome, as he asserts that through our voices, we might write a future that pushes against, stretches, and bends the structures of power designed to limit our freedom. To create opportunities where there are inherent constraints. We talk about finding our voices, but we talk less about how finding our voices means finding and writing freedom for ourselves and others.

An aside: In many ways, Long Division could only ever be written about the black South, because who time travels more than black southerners? Big K.R.I.T. time travels in “Praying Man.” When Kindred’s Dana goes back, Butler sends her to the South, to slavery. Erykah Badu is sure she’ll be there next lifetime. When I walk on the University of Mississippi campus and am greeted by towering Confederate statues or accidentally bump into Meredith’s statue behind the Lyceum, I time travel. When the University implicitly encourages students to put a noose on Meredith’s statue, I time travel. Time travel is necessitated by rupture, and therefore we are constantly in a state of temporal movement–or of flight like Morrison’s Milkman, or underground like Ellison’s protagonist and Laymon’s protagonists–because of our experiences and histories as black folks in the South.

Treatments of the South often fix the region in time and space. When return migrants are eager to “come home” to the South, they remember a respectable imagined community of all-black neighborhoods with doctors staying next door to factory workers. When southern expatriates in the North or West who plan never to return talk about the South, they point to the Jena 6 and Trayvon Martin and imagine country road ramblings and edge-of-town lynchings. When white Yankees think on the South, they remind themselves of their own relative goodness compared to Phil Robertson. The South is forever rural, forever 1964, sometimes forever slavery, which obscures the way it both is and is not those things. To say that the South ain’t changed and is all country is not true. But then neither is saying it has changed and is new and shiny and cosmopolitan. Long Division allows us to step directly into these tensions and be squeezed and pulled by the contradictions as we roller-coaster-jolt from 2013 to 1985 to 1964 and back again.

As if anything could be beyond what Laymon has done for race, temporality, geography, and the South—as well as for the real and transhistorical black southerner—there is also what Long Division does for questions of love, death, and dying. Across cities/Cities, there is the looming and encompassing quality of love that bends sexuality and familial boundaries. But there is also dying as the liminal space between love/life and death. In any given moment, Long Division argues, as long as one is loving, she or he can transcend the messiness that is a blues dying and get on to a blues death so one can be born and get back to living and loving again. Yet, the novel reminds us that sometimes it is extraordinarily hard to give up love for a greater good, or to delay love until the next lifetime, or to choose between things we love. As (semi-)free agents, we make these choices within a context of constraints and hostile structures, but we are under an extraordinary amount of pressure to get the choice right. Our future, and our past, depend upon it.

I imagine I’ll be writing, reading, reading about, and teaching Long Division for a long time. It is part of that hard work in the shed, of crafting and loving the region and the race, and of giving voice to ourselves to ensure a future freedom that we create. It is undoubtedly an invitation (and in many ways an imperative) for all of us with these black southern ontologies to get in the shed and get this work.

I just finished reading this, and the whole time, I wondered what you’d think about it. I did not grasp half of it the first time around.

You see I read it three times.