Gangsta Boo’s Enquiring Minds (1998) was the soundtrack to a season of fence-jumping feminism, a culmination of springs, summers, and falls spent fighting boys and finding our voices in communities that worked to silence the raucous and bulbous female parts of us. We had been anticipating the album, knowing full well Lola Mitchell’s refusal to be tucked and secreted, and also anxious about our need for her voice to confirm the black southern girl theory we conjured every day beyond boys’ earshot. And although Enquiring Minds was cluttered with boys’ voices, Gangsta Boo, the First Lady of Three Six Mafia, The Queen of Memphis, innovated, carved out space, clapped back, made history, and re-wrote history on those twenty-one tracks. She spoke to and for a range of us–the nerds, the pretty girls, the ‘hood chicks, the studs, the wealthy, the bohos, and all combinations of the preceding–as a black southern woman, a late 20th century voice from the South determining when and where she entered.

Gangsta Boo’s Enquiring Minds (1998) was the soundtrack to a season of fence-jumping feminism, a culmination of springs, summers, and falls spent fighting boys and finding our voices in communities that worked to silence the raucous and bulbous female parts of us. We had been anticipating the album, knowing full well Lola Mitchell’s refusal to be tucked and secreted, and also anxious about our need for her voice to confirm the black southern girl theory we conjured every day beyond boys’ earshot. And although Enquiring Minds was cluttered with boys’ voices, Gangsta Boo, the First Lady of Three Six Mafia, The Queen of Memphis, innovated, carved out space, clapped back, made history, and re-wrote history on those twenty-one tracks. She spoke to and for a range of us–the nerds, the pretty girls, the ‘hood chicks, the studs, the wealthy, the bohos, and all combinations of the preceding–as a black southern woman, a late 20th century voice from the South determining when and where she entered.

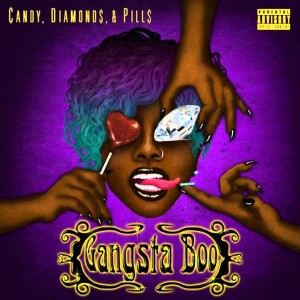

On her new mixtape, Candy, Diamonds, & Pills, the rapper reflects on this moment, compelling us to remember the history of her voice as a central and defining feature of the Memphis rap sound in general and of Three Six Mafia in particular. “I am Three Six Mafia; I was Three Six Mafia from day one,” she declares in a snippet of the phone interview on the mixtape, laying claim to her place in the group but also re-articulating herself in a musicological history from which she had been unceremoniously excised by the boys. “You can’t re-write history,” she argues in another part of the interview, challenging her erasure in revisionist and misogynist histories of her position in the group.

It isn’t only in these interview interstices that she makes this claim. On the short opening monologue on “Meet the Devil,” she situates herself directly in not only the musiciological history, but also the southern urban history that made Three Six Mafia possible:

Yeah, muhfuckas be talking that shit, talmbout, “Why [you] leave Da Mafia Six? Is boo in Triple Six?” Nigga [laughs]? I am Triple Six, fuck you talmbout? Mane, I grew up around the same shit the rest of the niggas grew up around. Fuck you mean.

“I am Triple Six,” she declares, revealing herself as the Trickster woman devil some of us are “meeting” and others of us are welcoming home. She is also strategically asserting that she is more than her association with the men, notably DJ Paul and Juicy J, of the group. Later in the first verse,

I ain’t gotta hang with DJ Paul to be reppin’ that Triple 6/I’m a pioneer up in this bitch/betta recognize who you be fucking with/with much respect, got the check, got the tec if somebody gotta problem with me/I was born in it, I’ma die in it/If you want me, then you betta try to come and get me.

Gangsta Boo does re-write history, albeit with the same corrective pen black women have used in response to their erasure since enslavement. With the production of Stunt N Dozier, she marshals a very specific black southern feminist sonic nostalgia–back to “1999,” the first track on the mixtape–to perform historiographical surgery on southern rap.

They say they want that real back? Then I gotcha/They say they want a trill bitch around? Then I gotcha/We gone take it back to 1999/Boy, this shit feel like it’s 1999/They say they miss that “yeah ho”? Then I gotcha/They say they want that old Boo back? Then I gotcha/Mane, this shit feel like it’s 1999/I’ma take it back to 1999.

This isn’t a male rap nostalgia, riddled with fragile masculinities, respectability politics, and hotep sensibilities. This is a grown woman’s nostalgia, a re-telling, a remembrance, full of the hindsight, respect, reflection, forgiveness, and yeah hos all real southern black grandmothers want their progeny to grow up to enjoy. In order to go forward, Gangsta Boo time travels to the point of departure and brings those of us who were there listening back into the future with her.

Boo is in all senses of the word a pioneer, and a working one at that, advocating for hardworking hustle women, the weed smoking women, the thuggin’ women who, as she describes herself in a collaboration with Big K.R.I.T. on a previous mixtape, “just wanna look good…just wanna have thangs…and make my grandmama proud of me.” Themes of historical reclamation sonically and lyrically anchor the mixtape; but Boo also confidently walks her corrections into the present. Like all black women historians, she. has. receipts. Her lyricism and voice have an enduring, familiar, and rooted quality, transcending the clatter of the revolving men’s voices that peppered Enquiring Minds. In fact, as the fates of some of the men of Three Six Mafia reflect the savages of inequality and the inevitability of the blues, with a corrected history in tow, Boo can claim distance and closeness, space and survival, and moreover persistence, in her own words.

Through her black southern feminist historiography of her particular experience in a particular group in a particular southern city, the Queen of Memphis has challenged black women’s erasure from all kinds of histories and pioneer statuses. She has once again made us, the fence-jumping black girls who did “everything the boys did,” visible and heard in a way that we otherwise might not be. She has reminded us to not lose sight of the things we pioneer, we hustle, in our everyday lives. She has also reminded us that it is in and through words, through discourse, that we wage the most basic of wars for our names.

Yeah ho.

Leave a Reply